Back To The Future: Peter Brock Revives The Daytona Coupe

By TOMMY PARRY OCTOBER 01, 2018

Convincing the discerning and traditionally minded team at Shelby was never going to be easy. Peter Brock, Carroll Shelby’s designer, had his work cut out for him when he proposed the new shape for what would become the Daytona in 1964. But, with the conviction of a man in possession of some real aerodynamic understanding, he vowed to shatter the conventions of the day.

Veteran car builders of the time swore by the widely accepted streamlined shapes established by Hungarian aerodnamicist Paul Jaray who, during WWI, mathematically determined the shape of the German Zeppelins. His theory on airflow was patented and copied (but seldom paid for) by almost every automotive manufacturer in the world, and it set the standard for the great “teardrop” shapes of the late ’30s which lasted until Brock and Ugo Zagato drove the game forward.

This way, 200 miles an hour on the Mulsanne Straight, in a Daytona, isn’t a lost dream — it’s still possible. — Peter Brock

Naturally, the Shelby team were reluctant to stray from the swooping lines of the original Cobra. However, Peter knew that a chopped rear design was necessary to improve straight-line speeds and high-speed stability at faster tracks like Le Mans, Spa, and Monza. However, when he proposed this unsightly alteration, Shelby’s crew responded with silence.

The unconventional roofline shocked the men at Shelby at first sight. (Note the highpoint of the roofline behind the driver’s head.)

To try and strengthen his cause, Peter cited a little-known German study on aerodynamics from a 1937, which convinced one of the more imaginative members of the group, Shelby’s lead driver Ken Miles, to back the idea and help build a 3D mock-up. To beat the Ferrari GTOs, Miles understood that superior aerodynamics were key — and that, eventually, the reluctant crew would eventually see the light. To build the car Shelby needed money. He couldn’t go to Ford as they were already working on a GT design of their own, so he turned to Goodyear, who agreed to fund the first Daytona.

The first auspicious outing took place on Feburary 1st, 1964, when Ken Miles, John Ohlsen, and Peter tested the car at Riverside. Blown away by the gains in top speeds, they phoned Carroll Shelby to make sure they’d been given the right gearing. They eclipsed the lap record and Shelby, once skeptical of the project, agreed to enter it at the Daytona 2000 K race.

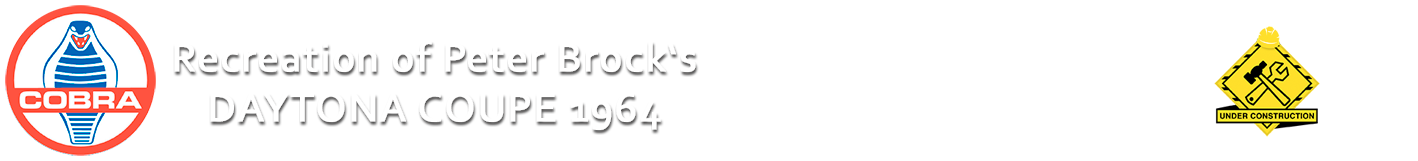

Craig Breedlove and Bobby Tatroe set world records at Bonneville in late 1965. (Photo Credit: Goodyear)

They then called Goodyear for wider rear tires to make better use of the Ford 289’s 385 horsepower. While the tire giant did not have the facilities to make something bespoke in the weeks before the car’s first race at Daytona, it was able to provide a set of contemporary NASCAR fronts, which the team squeezed underneath wider rear fenders.

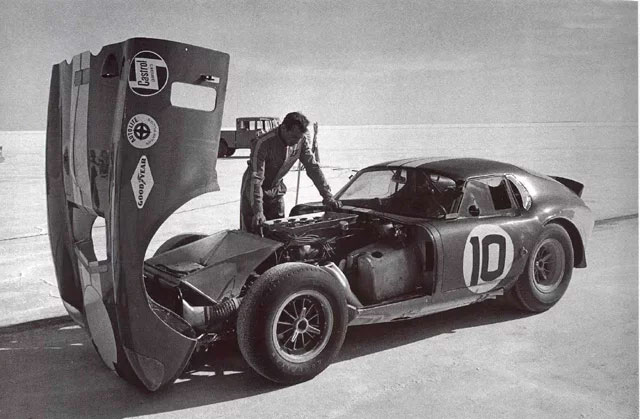

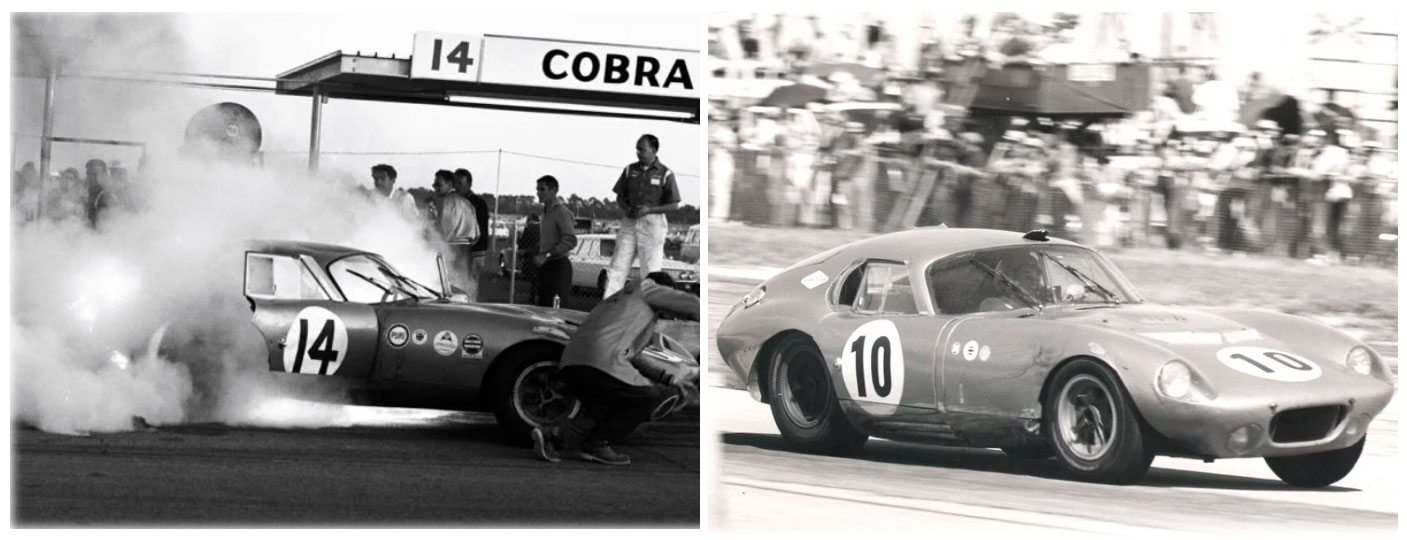

With optimized gearing, they hired Dave MacDonald and Bob Holbert to drive the car at its maiden race. During testing for Daytona, they realized their straight-line speeds were more than enough to blow the doors off the Ferraris, so they confidently lowered the redline and still set the lap record. However, their bliss wouldn’t last long. All was running well for the elated team until a refueling hiccup set the car alight and ended their race.

There were flames in Daytona, but Dave MacDonald (pictured, right) and co-pilot Bob Holbert scored the all-important GT Class win at Sebring. (Photo Credit: Dave Friedman)

Nevertheless, their potential was obvious, and for the following event, the 12 Hours of Sebring, was much more fruitful. There, they set the GT pole, took the fastest lap, and won the GT class. Now, with something to hang their hats on, they were able to continue the limited development of the car and take it across the Atlantic to show the Europeans how well the uncouth Yanks could race.

A Larger Goal

At the time, Henry Ford II had his eyes on expanding into the European market, and wanted an established race team to help. After attempting a $12M buyout of Ferrari, who reportedly reneged on the proposed deal quite late in the game, Ford was irate. He sought out a talented crew, and with the help of Eric Broadley, the GT40 project commenced.

Ford had been dedicating the bulk of the racing budget to the GT40 program, but once the Daytona proved its mettle by winning Sebring, he agreed to fund another five Daytonas. However, the budget was still quite tight and the team, consisting of just six mechanics, had its hands full racing the first car. So, Shelby shopped around for the crew that would build these next five for peanuts.

The job was contracted out to Carrozzeria Gransport, an Italian outfit which reportedly built each of these cars for the meager sum of $3,500 — and that was for a completed car with an interior. Adjusting for inflation, that’s roughly $28,000. A laughably good deal for a car which would eventually push Enzo Ferrari out of GT racing.

Note the difference in the roofline of the Italian shape. (Photo Credit: Daytona APS)

As the only existing Daytona was unavailable, the Italians only had Peter’s original drawings to go by. Without much involvement from the original team as well as a few errors in translation, due to a tendency to measure by eye and the old metric-imperial confusions, the Italians “adjusted” the roofline to mimic the Ferrari GTO’s. This, understandably, became a cause for some frustration with Peter. Since this was the factor most responsible for the original Daytona’s speed.

With no time to change before he roofline before Le Mans, the first Italian car was left as it was, which would worsen drag. Because there was no time to test prior to the 24 Hours, the team weren’t aware of this difference in speed until the race was well underway.

A Frantic Debut Abroad

In fact, when the Daytona debuted at Le Mans in 1964, they brought both the American-built car and one of the Italian creations. The American machine was driven by Jochen Neerpasch and Chris Amon, while the Italian car was manned by Dan Gurney and Bob Bondurant. At the end of the Mulsanne Straight, the differences in aerodynamics made themselves clear: the Italian car hit 191 miles an hour at the Mulsanne Straight — 6 miles an hour slower than the American car!

The American car was leading the GT class and sandwiched in the middle of the prototypes. Despite the commanding pace and a staggering first-time performance, a minor mechanical gremlin nearly sidelined their efforts. John Ohlsen, who was acting as crew chief on the Italian car, had installed new fan belts, which stretched by the tenth hour. Without the tension needed to keep the generator charged, the headlights were enough to sap the last drops of juice from the battery.

When the car pitted for fuel, it wouldn’t turn over. Unfortunately, as per the Automobile Club de l’Ouest rules of the day, the car had to start under its own power. While the lead marshal had given the team cryptic instructions on how to bend the rules, charge the car momentarily, and then crank it over with a few drops in the battery, the team misunderstood this stealthy advice. As soon as they threw on the jumpers, Ferrari protested and had the American Daytona disqualified.

Bondurant leans his way around Le Mans in 1964. (Photo Credit: Clubcobra.com)

The fortunes for the Italian car were better, though far from perfect. After taking a rock through the oil cooler in the night, Dan Gurney came in, complaining of instability caused by a mist of oil over the rear tires. They bypassed the cooler and ran the engine quite hot. Though this was a quick fix, this premature stop hampered the car’s progress in another way. For the number of laps Dan had completed, he was not allowed to add any oil. So, he spent the next few, frustrated laps crawling and swerving to avoid starving the pickup.

Once past the mandatory number of laps, he refueled and continued his charge despite having to limit revs to prevent overheating. In the end, it was enough to lead the GT class to the end of the race. The double points offered at Le Mans helped Shelby steal the points lead from Ferrari with that victory. Unfortunately, Ferrari claimed the title at the end of the season, but needed to resort to some political strongarming to do so.

“Ferrari induced the Auto Club de Italia to cancel the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile points for the final event at Monza, knowing he’d get his doors blown off with four Daytonas entered. Naturally, Ferrari would have lost the championship; an unforgivable sin at Monza, where Enzo’s team hadn’t lost a GT race in five years,” Peter recalled with a smirk and a shake of the head.

However, Shelby finished runner-up in the championship, which made him an accepted name worldwide. The following season, the team made good, wiped the floor with the Prancing Horse, and the Daytona legend was solidified.

Fast Forward 50 Years

(Left to right) Brock, Tarne, and Ebner posing with their new creation. (Photo Credit: Gruppe C Photography)

For the next five decades, numerous second-rate replicas — most often in the Italian shape — sprouted up, causing some aficionados to wonder what ever happened to the original six. Among those were a couple influential individuals who sought to see the originals run together. So, at the behest of Charles Gordon-Lennox, the 11th Duke of Richmond, the six were assembled at the Goodwood Revival in 2015, then scattered once again to all corners of the globe.

This sparked the interest of Mikael Tarne and Bastian Ebner, two avid enthusiasts, who got in touch with Peter. Soon, the three were discussing the differences between the American and Italian cars, and how one would go about building a replica to do the original American-built justice.

CSX 2287, the American-built car, posing among its siblings at the Goodwood Revival in 2015. Photo credit: Randy Richardson

To do this, they couldn’t rely on Peter’s drawings alone — they needed to find the original cars. Fortunately, locating them wasn’t too challenging. Car #CSX2299, the original Italian car, is in the possession of the Miller family, who gladly offered it for 3D scanning. Car #CSX2287, the American-built original, belongs to Fred Simeone, who only too was happy to help continue the car’s saga.

Scanning The Past

Soon, the trio established a company, Daytona Coupes ApS, to turn these scans into perfect replicas for the European vintage racing market. Each one of these cars is overseen by Peter, who personally fits his own designer badges to them. Thanks to 3D scanning, these replicas share to the exact shape of originals, though the aluminum alloy body panels are still built in the traditional, hand-crafted style.

Brock oversees the shaping of each body panel; ensuring they perfectly mimic the originals. (Photo Credit: Daytona ApS)

The Ford 289 motor is made with Shelby components to adhere exactly to vintage spec and certified for FIA racing. The gearbox, a BorgWarner T-10 fitted with special competition ratios, sends power back to a Salisbury-type case with a limited-slip differential suitable for competition. The modern creation mimics the original car in every way, except for the modern safety equipment necessary for FIA certification.

The replica uses Dunlop-style, single-piston alloy calipers on vented steel discs underneathHalibrand style alloy racing wheels. Photo credit: Gruppe C Photography

The Italian replica was built, compared to the original Carrozzeria drawings, and proven to be identical. The car was taken to the Nürburgring, where it acted as the pace car for the Nürburgring Classic in 2018. For the first time in 50 years, a car sharing the exact dimensions of the original car was driven in anger — and without fear of a multi-million dollar repair bill.

The 2299 Coupe leading the field at the Nürburgring in 2018. (Photo Credit: Gruppe C Photography)

The reality of the matter is that, even those lucky few who can drive the originals on the circuit feel the need to leave some in reserve. It’s a pity, but an understandable one, as the Daytona is a car unrestrained by downforce or modern nannies; a raw thoroughbred which dances with the driver. With little weight, great balance, and gobs of torque, the natural yaw and sway of a Daytona driven to and beyond the limit of adhesion is something any automotive enthusiast needs to see.

Which is exactly where Peter and his stellar replicas come in.

“Today’s downforce has made some racing spectacles boring to watch — which is a large part of why vintage racing is so popular,” he said. “The current cost of owning and racing a legend is so prohibitive that few can even consider acquiring such a car. Still, the thrill of racing high-revving Italian V12s against English inline-6s or stock block-based American V8s never gets old. That’s why we’re building FIA-legal replicas of the Daytona Cobra Coupes for top vintage events. This way, 200 miles an hour on the Mulsanne Straight, in a Daytona, isn’t a lost dream — it’s still possible.”